A Remarkable Offer

“I’ve been a teacher all my life”, Grover Krantz once said. “And I think I might as well be a teacher after I’m dead, so why don’t I just give you my body.”

With those words, Krantz – an anthropologist, professor, and the first academic to seriously study Bigfoot – made a decision that would shape his legacy long after his passing.

A Life of Curiosity and Devotion

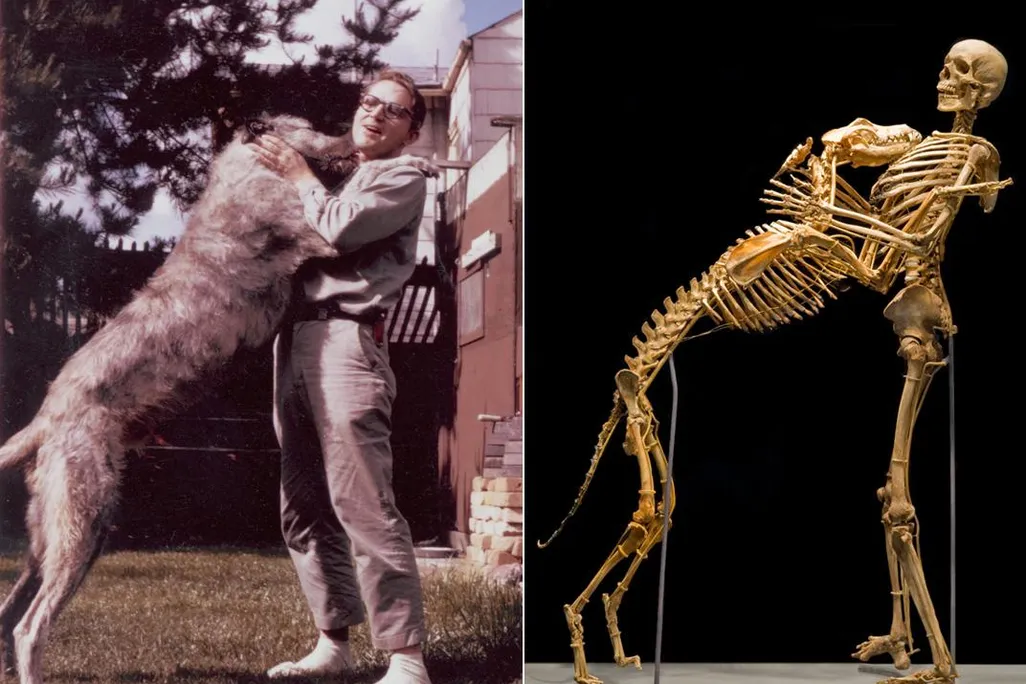

Grover Krantz (1931–2002) was known for his eccentric mind, deep love for his pets, and decades of teaching. Seven years after his death from pancreatic cancer, his reputation remains alive in an extraordinary way.

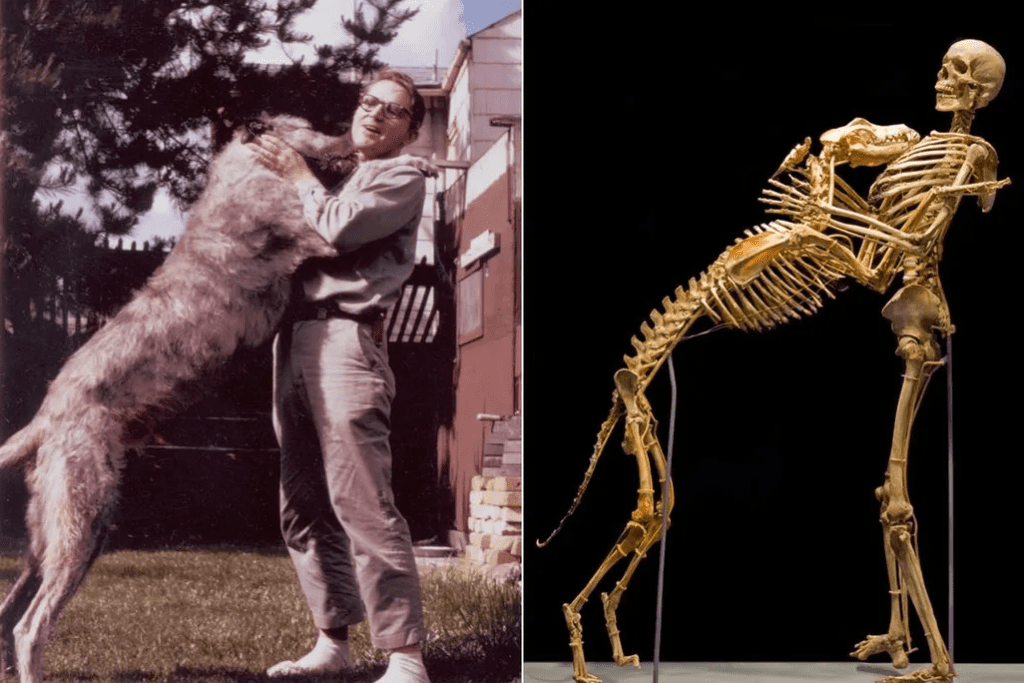

Today, the skeletons of Krantz and his beloved Irish Wolfhound, Clyde, are displayed together in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History at the “Written in Bone: Forensic Files of the 17th-Century Chesapeake” exhibition.

Teaching Through Bones

The exhibit invites visitors into the world of forensic anthropology, where bones become storytellers, revealing secrets of the colonial Chesapeake and offering clues in modern-day investigations, such as war crimes in Croatia.

At the end of the exhibit, visitors encounter Krantz and Clyde displayed in a tender pose, symbolizing how body donations help train future scientists.

The Only Condition: Keep My Dogs With Me

Before his death, Krantz made a unique request to Smithsonian anthropologist David Hunt. When Hunt agreed to receive his body, Krantz added one condition:

“But there’s one catch: You have to keep my dogs with me.”

After Krantz passed away, there was no funeral. His body was transported to the University of Tennessee’s famous body farm, where researchers study human decomposition to advance forensic science. Later, his remains, and those of his wolfhounds, were moved to the museum’s vast storage halls, alongside dinosaur fossils. Hunt even preserved Krantz’s baby teeth.

Colleagues Remember a Brilliant Mind

The inclusion of Krantz’s skeleton adds a deeply personal touch to “Written in Bone”. The exhibit’s co-curators, Douglas Owsley and Kari Bruwelheide, two leading forensic anthropologists, had worked closely with Krantz.

He also played a key role in the Kennewick Man case, one of the most significant, and controversial, discoveries of Owsley’s career. Krantz was among the experts advocating for the scientific study of the 8,400-year-old skeleton found in Washington State.

A Teacher Forever

Krantz spent his life educating others, and now, through the exhibit, he continues teaching in death. For the next two years, visitors will encounter his bones and learn from the lessons they offer, just as he intended.