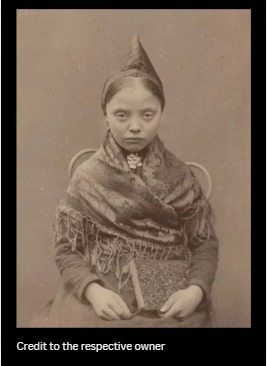

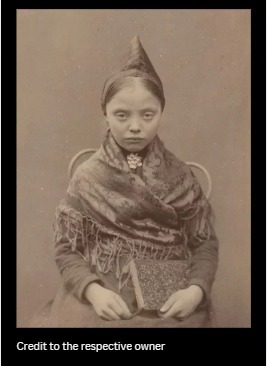

Paris, 1889. Amid cages of exotic animals and so-called “human exhibits,” a young girl with a calm, steady gaze posed for the lens of a French prince. Her name was Sigrid Olsdatter, just eleven years old, and she belonged to the Sámi people—indigenous inhabitants of the European Arctic whose ancestral lands stretch across the snowy regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia.

She wore a traditional shawl and held a notebook tightly in her hands, as if the weight of her story rested within its blank pages. Atop her head sat a distinctive pointed hat, a tjurrietiohpe, a sacred symbol of Sámi heritage, womanhood, and family lineage. To the colonial gaze, she was a subject of study—a curiosity—but to her people, she was a living thread in a tapestry of survival, spirit, and culture.

Though photographed by Roland Bonaparte under the guise of “scientific” documentation, Sigrid’s portrait resisted erasure. The lens could not dim her quiet dignity. In that still image, she became a silent testament to a resilient people. She does not look at us with fear or submission, but with the steady poise of someone who knows: history does not always belong to the one holding the pen.