A 37-year-old immigrant died penniless in 1889—but his invention is in every shoe you’ve ever worn.

In 1880, a pair of shoes cost more than most families earned in a week.

Not because leather was expensive. Not because cobblers were greedy. But because of one impossible step in the shoemaking process that no one—not a single inventor in the world—could figure out how to mechanize.

It was called “lasting”—attaching the upper part of the shoe to the sole. It required such extraordinary precision that only the most skilled craftsmen could do it. They could make about 50 pairs a day. And they knew they were irreplaceable.

Dozens of inventors had tried to build a machine to do this work. All of them failed. The process was too complex, too delicate, too… human.

Then a young man who barely spoke English decided to solve it.

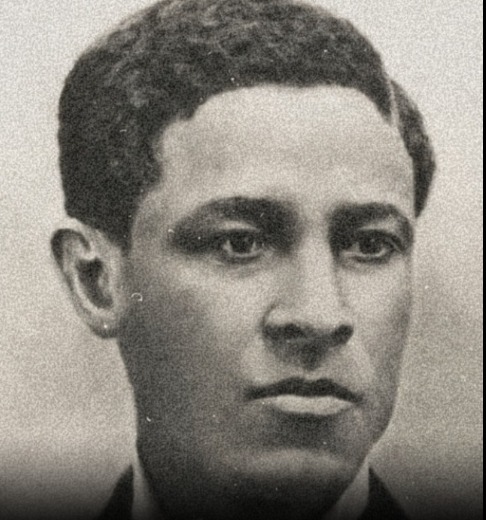

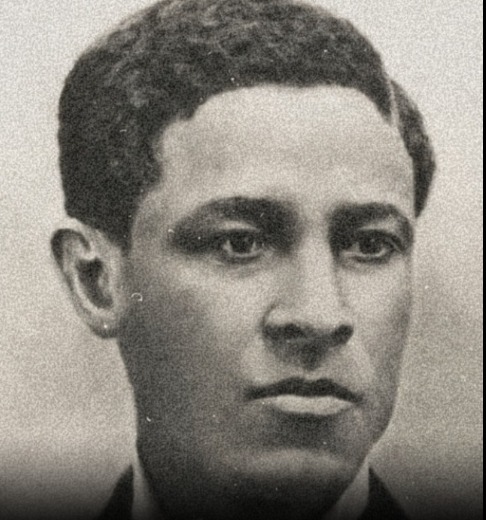

Jan Ernst Matzeliger was born in Suriname in 1852 to a Dutch father and Black Surinamese mother. As a teenager, he worked in machine shops, falling in love with gears, levers, and the logic of mechanical systems.

At 19, he left home to work on ships. Two years later, he landed in Lynn, Massachusetts—the shoe capital of America. He found work in a factory and immediately saw the bottleneck that was strangling the entire industry.

He also saw that no one thought a Black immigrant machinist could solve it.

Matzeliger worked 10-hour factory shifts. Then he went home and taught himself English from books. He taught himself mechanical drawing. He taught himself advanced engineering—all by candlelight, all while exhausted.

And he started building.

For six years, he designed, built, tested, and failed. Model after model. Investors laughed at him. Fellow workers doubted him. As a Black man in 1880s America, doors that should have opened stayed closed.

But on March 20, 1883, the United States Patent Office issued Patent No. 274,207 to Jan Ernst Matzeliger.

His lasting machine worked.

It wasn’t just a little better than human hands—it was transformational. Where the best craftsmen made 50 pairs a day, Matzeliger’s machine could produce 150 to 700 pairs, depending on the model. It worked faster, more consistently, and never got tired.

Within years, shoe prices dropped by half. For the first time in human history, working families could afford well-made, durable footwear. Children’s feet could be protected. Workers could have shoes that lasted.

One man’s invention had changed daily life for millions.

But Matzeliger never saw the full impact.

To get his machine into production, he had to sell controlling interest to investors. They made fortunes. He received modest payment and stock. The machine became part of the United Shoe Machinery Corporation, which dominated the global industry for decades.

Matzeliger kept working, kept refining, kept improving. But the years of 16-hour days, the stress, the poor working conditions—they caught up with him.

He contracted tuberculosis. In 1889, without access to proper medical care, weakened by years of overwork, Jan Ernst Matzeliger died.

He was 37 years old.

He lived only six years after his patent. He never became wealthy. He never became famous. The men who profited from his genius lived to old age and prominence, celebrated as industry visionaries.

The Black immigrant who actually solved the impossible problem? Forgotten.

For over 100 years, his name was virtually unknown. It wasn’t until 1991—more than a century after his death—that he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

But here’s the thing: even though history forgot him, his invention never stopped working.

Every mass-produced shoe made in the last 135 years uses the principles Jan Ernst Matzeliger developed in that cramped room after his factory shifts. Every pair of sneakers. Every pair of dress shoes. Every pair of boots.

He came to America speaking no English. He taught himself engineering from books. He worked a brutal factory job while inventing at night. He faced racism, poverty, and skepticism at every turn.

And he solved a problem that everyone—everyone—said was impossible.

He made shoes affordable for the world. He changed what it meant to be poor in America, because for the first time, working people could afford the basic dignity of good footwear.

Jan Ernst Matzeliger died young, poor, and forgotten. But his legacy walks with every person on Earth.

Every step you take is possible because a young man from Suriname refused to believe that impossible meant impossible.

His name should be as famous as Edison. As celebrated as Ford. But it’s not.

Not yet.

Now you know: Jan Ernst Matzeliger, 1852-1889. The man who put the world on its feet.